what is an easy painless way to commit suicide

A suicide method is any means by which a person chooses to stop their life. Suicide attempts exercise not ever result in expiry, and a nonfatal suicide attempt tin exit the person with serious physical injuries, long-term wellness problems, and brain harm.[ane]

Worldwide, three suicide methods predominate with the blueprint varying in different countries. These are hanging, poisoning by pesticides, and firearms.[ii] Other common suicide methods include jumping from a great superlative, drug overdoses, and drowning.[3] [four]

Suicides are often impulse decisions that may be preventable by removing the ways.[five] Making common suicide methods less attainable leads to an overall reduction in the number of suicides.[6] [seven] Some ways to do this include restricting access to pesticides, firearms, and known-used drugs. Other important measures are the introduction of policies that accost the misuse of booze and the treatment of mental disorders.[eight] Gun-control measures in a number of countries have seen a reduction in suicides and other gun-related deaths.[ix]

Purpose of report

The report of suicide methods aims to identify those commonly used, and the groups at chance of suicide; making methods less accessible may be useful in suicide prevention.[half dozen] [5] [10] Limiting the availability of means such equally pesticides and firearms is recommended by a Earth Wellness Report on suicide and its prevention. The early identification of mental disorders and substance abuse disorders, follow-up care for those who have attempted suicide, and responsible reporting past the media are all seen to be primal in reducing the number of deaths by suicide.[11] National suicide prevention strategies are also advocated using a comprehensive and coordinated response to suicide prevention. This needs to include the registration and monitoring of suicides and attempted suicide, breaking figures down by age, sex, and method.[eleven]

Such information allows public wellness resources to focus on the bug that are relevant in a particular place, or for a given population or subpopulation.[12] For example, if firearms are used in a pregnant number of suicides in one place, then public health policies there could focus on gun condom, such every bit keeping guns locked away, and the key inaccessible to at-chance family unit members. If immature people are establish to be at increased risk of suicide by overdosing on detail medications, then an alternative class of medication may be prescribed instead, a safety plan and monitoring of medication tin exist put in place, and parents can be educated well-nigh how to forbid the hoarding of medication for a futurity suicide effort.[x]

Media reporting

Media reporting of the methods used in suicides is "strongly discouraged" by the Earth Health System, government wellness agencies, universities, and the Associated Press amidst others.[thirteen] Detailed descriptions of suicides or the personal characteristics of the person who died contribute to copycat suicides (suicide contagion).[14] [15] Dramatic or inappropriate descriptions of individual suicides past mass media has been linked specifically to copycat suicides among teenagers.[15] Writing for the New Yorker about celebrity suicides, Andrew Solomon wrote that "You who are reading this are at statistically increased hazard of suicide right now."[16] In one study, changes in how news outlets reported suicide reduced suicides by a detail method.[15]

Media reporting guidelines also use to "online content including citizen-generated media coverage". The Recommendations for Reporting on Suicide, created past journalists, suicide prevention groups, and internet safety not-profit organizations, encourage linking to resources such as a list of suicide crisis lines and information about adventure factors for suicide, and reporting on suicide as a multi-faceted, treatable health effect.[17]

Method brake

Method restriction, as well chosen lethal means reduction, is an effective way to reduce the number of suicide deaths in the short and medium term.[18] Method restriction is considered a best practice supported by "compelling" evidence.[xv] Some of these actions, such as installing barriers on bridges and reducing the toxicity in gas, require action past governments, industries, or public utilities. At the individual level, method brake tin be as unproblematic every bit asking a trusted friend or family member to shop firearms until the crisis has passed.[19] [20] Choosing not to restrict admission to suicide methods is considered unethical.[15]

Method restriction is effective and prevents suicides.[15] It has the largest effect on overall suicide rates when the method being restricted is common and no direct exchange is available. [15] If the method existence restricted is uncommon, or if a substitute is readily available, and so it may be effective in individual cases but not produce a large-scale reduction in the number of deaths in a country.[15]

Method exchange is the process of choosing a different suicide method when the beginning-option method is inaccessible.[5] In many cases, when the commencement-choice method is restricted, the person does non try to find a substitute.[15] Method substitution has been measured over the grade of decades, so when a mutual method is restricted (for example, by making domestic gas less toxic), overall suicide rates may be suppressed for many years.[5] [fifteen] If the kickoff-option suicide method is inaccessible, a method substitution may be made which may be less lethal, tending to result in fewer fatal suicide attempts.[5]

In an case of the curb cut effect, changes unrelated to suicide accept also functioned equally suicide method restrictions.[15] Examples of this include changes to align railroad train doors with platforms, switching from coal gas to natural gas in homes, and gun control laws, all of which have reduced suicides despite existence intended for a different purpose.[fifteen]

List

Suffocation

Suffocation, as a classification of suicide method, includes strangulation and hanging.[21] [22]

Suicide by suffocation involves restricting breathing or the corporeality of oxygen taken in, causing asphyxia and eventually hypoxia. This may involve the use of a plastic suicide bag.[23] It is not possible to die simply by holding the breath, since a reflex causes the respiratory muscles to contract, forcing an in-jiff, and the re-establishment of a normal breathing rhythm.[24] Therefore, inhaling an inert gas such as helium, nitrogen, and argon, or a toxic gas such every bit carbon monoxide, is used to bring nearly unconsciousness.[25] [26] As of 2010[update], organizations supporting a right to die used death past helium inhalation more often than drug overdoses, largely owing to its reliability.[27]

Suicide past strangulation is self-strangulation that may involve the partial suspension of the trunk rather than the full pause used in hanging. Cocky-strangulation involves tightening a ligature around the neck. This compresses the carotid arteries, preventing the supply of oxygen to the brain, resulting in unconsciousness and decease.

Hanging

Hanging is a common method of suicide.[22] [21] Hanging involves the utilize of a ligature such as a rope or cord fastened to an anchor point with the other end used to class a noose placed around the neck. The crusade of death will either be due to strangulation or a cleaved cervix. About half of attempted suicides by hanging result in expiry.[iv] People who favor this method are usually unaware that it is often a "tiresome, painful, and messy method that needed technical knowledge".[28]

Hanging is the prevalent means of suicide in impoverished pre-industrial societies, and is more than common in rural areas than in urban areas.[29] It is also a common means of suicide in situations where other materials are not readily available, such as in prisons.

Hanging was the most common method in traditional Chinese culture,[30] as it was believed that the rage involved in such a decease permitted the person'due south spirit to haunt and torment survivors.[31] [32] In the Chinese civilisation, suicide by hanging was used equally an human activity of revenge past women[33] and of defiance past powerless officials, who used it as a "final, only unequivocal, manner of continuing withal against and above oppressive regime".[thirty] Chinese people would often approach the human activity ceremonially, including the use of proper attire.[30]

Poisoning

Suicide by poisoning, besides called self-poisoning, is ordinarily classed as a drug overdose when drugs such every bit painkillers or recreational drugs are used. The use of pesticides to cocky-poison is the virtually common method used in some countries.[ii] Inhalation of poisonous gases such every bit carbon monoxide may besides exist a cause of death by suicide. Poisoning through the means of toxic plants is normally slow and painful.[34] [ better source needed ] The mass suicide of members of a cult led past Jim Jones in 1978 resulted from poisoning ("Drinking the Kool-Aid").[35] [ better source needed ]

Pesticide

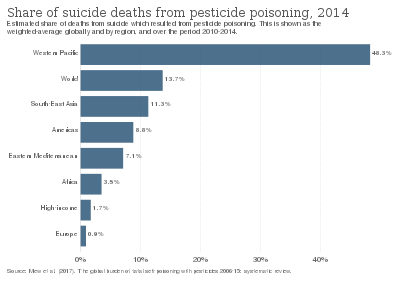

Share of suicide deaths from pesticide poisoning[36]

As of 2006[update], worldwide, effectually xxx% of suicides were from pesticide poisonings.[37] The use of this method varies markedly in different areas of the world, from 0.ix% in Europe to about 50% in the Pacific region.[36] In the US, pesticide poisoning is used in about 12 suicides per yr.[38] Poisoning past farm chemicals is very common among women in rural China, and is regarded equally a major social problem in the land.[39]

Method restriction has been an constructive way to reduce suicide by poisoning in many countries. In Finland, limiting access to parathion in the 1960s resulted in a rapid turn down in both poisoning-related suicides and full suicide deaths for several years, and a slower decline in subsequent years.[40] In Sri Lanka, both suicide by pesticide and total suicides declined later first toxicity class I and later course II endosulfan were banned.[41] Overall suicide deaths were cut by 70%, with 93,000 lives saved over 20 years as a effect of banning these pesticides.[2] In Korea, banning a single pesticide, paraquat, halved the number of suicides by pesticide poisoning[two] and reduced the total number of suicides in that country.[40]

Drug overdose

A drug overdose involves taking a dose of a drug that exceeds condom levels. In the Great britain (England and Wales) until 2013, a drug overdose was the most common suicide method in females.[42] In 2019 in males the percentage is 16%. Cocky-poisoning accounts for the highest number of non-fatal suicide attempts. Overdose attempts using painkillers are amid the near common, due to their easy availability over-the-counter.[43] Paracetamol is the virtually widely used analgesic worldwide and is unremarkably used in overdose attempts.[44] Paracetamol poisoning is a common cause of acute liver failure.[45] [44] In the The states about threescore% of suicide attempts and 14% of suicide deaths involve drug overdoses.[4] The take chances of expiry in suicide attempts involving overdose is about two%.[4] [ verification needed ]

A drug overdose is oft the first-choice method of members of correct-to-die organizations. A poll among members of Leave International suggested that 89% would prefer to take a pill, rather than use a plastic exit purse, a carbon monoxide generator, or wearisome euthanasia.[46] [47]

Carbon monoxide

A particular type of poisoning involves the inhalation of loftier levels of carbon monoxide (CO). Decease unremarkably occurs through hypoxia. Carbon monoxide is used because it is hands bachelor. A nonfatal attempt can effect in retentiveness loss and other symptoms.[48] [ self-published source? ] [49]

Carbon monoxide is a colorless and odorless gas, so its presence cannot be detected by sight or smell. Information technology acts past binding preferentially to the hemoglobin in the bloodstream, displacing oxygen molecules and progressively deoxygenating the blood, eventually resulting in the failure of cellular respiration and death. Carbon monoxide is extremely dangerous to bystanders and people who may discover the torso, so "Right to Die" advocates like Philip Nitschke recommend confronting information technology.[l] [ self-published source? ]

Earlier air quality regulations and catalytic converters, suicide past carbon monoxide poisoning was ofttimes accomplished by running a car's engine in an enclosed space such equally a garage, or past redirecting a running car'south exhaust back inside the motel with a hose. Motor car frazzle may have contained upward to 25% carbon monoxide. Catalytic converters constitute on all modern automobiles eliminate over 99% of carbon monoxide produced.[51] Every bit a further complexity, the amount of unburned gasoline in emissions can brand exhaust unbearable to exhale well earlier a person loses consciousness.

Charcoal-called-for suicide induces death from carbon monoxide poisoning. Originally used in Hong Kong, it spread to Nihon,[52] where small-scale charcoal-burning heaters (hibachi) or stoves (shichirin) have been used in a sealed room. Past 2001, this method accounted for 25% of deaths from suicide in Japan.[53] It has become the second most common suicide method in Hong Kong and is a growing trend in other countries.[52] Nonfatal attempts tin outcome in severe brain harm due to cerebral anoxia.

Other toxins

Detergent-related suicide involves mixing household chemicals to produce poisonous gases.[54] [ better source needed ] At the end of the 19th century in Britain, there were more suicides from carbolic acid (a disinfectant) than from any other toxicant since at that place was no restriction on its sale. Braxton Hicks and other coroners called for its sale to be prohibited in 1893.[55] [56]

The suicide rates by domestic gas roughshod from 1960 to 1980, as changes were fabricated to the formula to go far less lethal.[5] [57]

Shooting

Comparison of gun-related suicide rates to non-gun-related suicide rates in high-income OECD countries, 2010, countries in graph ordered by total suicides. The US was the only OECD country in which gun suicide rates exceeded non-gun suicide rates.[58]

Suicide rate past firearm[59]

In the United States suicide past firearm is the most lethal method of suicide resulting in ninety% of suicide fatalities,[iv] and is thus the leading cause of decease by suicide every bit of 2017.[threescore] Worldwide, firearm prevalence in suicides varies widely, depending on the acceptance and availability of firearms in a civilisation. The use of firearms in suicides ranges from less than 10% in Australia[61] to fifty.5% in the U.South., where it is the nearly common method of suicide.[62]

Generally, the bullet will be aimed at point-blank range. Surviving a self-inflicted gunshot may result in severe chronic pain every bit well as reduced cognitive abilities and motor part, subdural hematoma, strange bodies in the head, pneumocephalus and cerebrospinal fluid leaks. For temporal bone directed bullets, temporal lobe abscess, meningitis, aphasia, hemianopsia, and hemiplegia are common late intracranial complications. As many as fifty% of people who survive gunshot wounds directed at the temporal bone endure facial nerve harm, usually due to a severed nerve.[63]

Gun control

Reducing access to guns at a population level decreases the risk of suicide past firearms.[64] [65] [66]

Fewer people die from suicide overall in places with stricter laws regulating the use, purchase, and trading of firearms.[67] [68] Suicide take chances goes up when firearms are more bachelor.[69] [lxx] [71]

Gun control is a main method of reducing suicide by people who live in a habitation with guns. Prevention measures include simple deportment such every bit locking all firearms in a gun rubber or installing gun locks.[20] Some stores that sell guns provide temporary storage as a service; in other cases, a trusted friend or family member will offering to store the guns until the crisis has passed.[19] [20] When a person is going through a crisis, red flag laws in some places allow family unit members to petition the courts to have firearms temporarily removed and stored elsewhere.

More firearms are involved in suicide than are involved in homicides in the United States. A 1999 study of California and gun mortality constitute that a person is more than likely to die by suicide if they have purchased a firearm, with a measurable increase of suicide by firearm first at most a calendar week subsequently the buy and continuing for half dozen years or more.[72]

The U.s. has both the highest number of suicides and firearms in circulation in a developed state, and when gun ownership rises so besides does suicide involving the use of a firearm.[73] [74] A 2004 report by the National Academy of Sciences found an association between estimated household firearm ownership and gun suicide rates,[75] [76] though a written report by 2 Harvard researchers did not observe a statistically significant association between household firearms and gun suicide rates,[77] except in the suicides of children aged v–14.[77] Another written report found that gun prevalence rates were positively associated with suicide rates among people aged xv to 24, and 65 to 84, but not among those aged 25 to 64.[78] Case-control studies conducted in the United States have consistently shown an association between guns in the home and increased suicide risk,[79] specially for loaded guns in the domicile.[80] Numerous ecological and time series studies have likewise shown a positive clan between gun ownership rates and suicide rates.[81] [82] [83] This clan tends to only exist for firearm-related and overall suicides, not for non-firearm suicides.[82] [84] [85] [86] A 2013 review establish that studies consistently found a relationship between gun ownership and gun-related suicides, with few exceptions.[87] A 2016 study found a positive association between gun ownership and both gun-related and overall suicides amongst men, but not amid women; gun buying was only strongly associated with gun-related suicides among women.[88] During the 1980s and early on 1990s, there was a stiff upwards trend in adolescent suicides with a gun,[89] too as a sharp overall increase in suicides among those age 75 and over.[90] A 2014 systematic review and meta-assay found that access to firearms was associated with a higher gamble of suicide.[91]

A 2006 report found an accelerated pass up in firearm-related suicides in Australia afterward the introduction of nationwide gun control. The same written report found no show of substitution to other methods.[92] Multiple studies in Canada found that gun suicides declined later gun command, simply methods like hanging rose leading to no change in the overall rates.[93] [94] [95] Similarly, a study conducted in New Zealand found that gun suicides declined later more than legislation, merely overall suicide rates did not alter.[96] A example-control written report in New Zealand found that household gun buying was associated with gun suicides, but not overall suicide.[97] The authors attributed this finding to the highly stringent firearm storage laws and very low prevalence of handgun buying in New Zealand. A Canadian report found that gun ownership by province was not correlated to provincial overall suicide rates.[98] A 2020 study as well plant no significant correlations between provincial firearm ownership and overall provincial suicide rates.[99]

Jumping

Jumping from a unsafe location, such as from a loftier window, balcony, or roof, or from a cliff, dam, or span, is an frequently used suicide method in some countries. Many countries have noted suicide bridges such as the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge (China) and the Aureate Gate Bridge (Us). Other well known suicide sites for jumping from include the Eiffel Tower (France), Beachy Caput (United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland)[100] and Niagara Falls (Canada).[101] Nonfatal attempts in these situations tin can take severe consequences including paralysis, organ damage, and broken bones.[102]

In the United States, jumping is among the least common methods of suicide (less than ii% of all reported suicides in 2005).[103] In a 75-yr period to 2012, in that location were around 1,400 suicides at the Gilded Gate Bridge. In New Zealand, secure fencing at the Grafton Span essentially reduced the rate of suicides.[104]

Jumping is the most common method of suicide in Hong Kong, bookkeeping for 52.1% of all reported suicide cases in 2006 and similar rates for the years earlier that.[iii] The Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention of the University of Hong Kong believes that it may be due to the abundance of easily attainable high-rise buildings in Hong Kong.[105]

Cut and stabbing

Cocky-inflicting a wound with a precipitous instrument equally a suicide method is usually to the wrists only can likewise exist to the throat (or abdomen in harakiri). The wounding of the wrists is a relatively common method of attempting suicide, and the ready availability of knives is a noted cistron.[106] A fatal self-inflicted wound to the wrist is termed a deep wrist injury, and is often preceded past several tentative surface-breaking attempts known as hesitation wounds, indicating indecision or a self-harm tactic.[107] For every suicide past wrist cutting, there are many more than nonfatal attempts, then that the number of actual deaths using this method is very low.[108]

Wounds from suicide attempts involve the non-ascendant manus, with damage frequently done to the median nerve, ulnar nervus, radial artery, palmaris longus muscle, and flexor carpi radialis musculus.[109] [107] Such injuries can severely affect the part of the mitt, and the inability acquired to carry out piece of work or interests increases the risk of further attempts.[107]

Drowning

Suicide by drowning is the human action of deliberately submerging oneself in h2o or other liquid to foreclose breathing. It accounts for less than two% of all suicides in the Us.[103] Of those who attempt suicide past drowning in the United states of america, most half dice.[4]

Starvation and dehydration

A classification has been fabricated of Voluntary Stopping Eating and Drinking (VSED) which is often resorted to in concluding illness.[110] [111] This includes fasting and dehydration, and has also been referred to as autoeuthanasia.[112]

Fasting to expiry has been used by Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain ascetics and householders, every bit a ritual method of suicide known equally Prayopavesa in Hinduism; Sokushinbutsu historically in Buddhism; and as Sallekhana in Jainism.[113] [114] [115] Cathars also fasted to death after receiving the consolamentum sacrament, in social club to die while in a morally perfect state.[116] This method of death is also associated with the political protest of the hunger strike such as the 1981 Irish hunger strike in which ten prisoners died.

The explorer Thor Heyerdahl refused to eat or have medication for the terminal calendar month of his life, later he was diagnosed with cancer.[117]

Death from dehydration can have from several days to a few weeks. This means that unlike many other suicide methods, it cannot be achieved impulsively. Those who die by terminal aridity typically lapse into unconsciousness before death, and may likewise feel delirium and deranged serum sodium.[118]

Terminal aridity has been described as having substantial advantages over physician-assisted suicide with respect to self-determination, access, professional integrity, and social implications. Specifically, a patient has a correct to decline treatment and it would exist a personal assault for someone to force water on a patient, merely such is non the case if a doctor only refuses to provide lethal medication.[119] But it also has distinctive drawbacks as a humane means of voluntary death.[120] One survey of hospice nurses found that nearly twice equally many had cared for patients who chose voluntary refusal of nutrient and fluids to hasten decease as had cared for patients who chose physician-assisted suicide.[121] They also rated fasting and dehydration as causing less suffering and pain and being more peaceful than dr.-assisted suicide.[122] [111] Other sources notation very painful side effects of dehydration, including seizures, pare corking and bleeding, blindness, nausea, airsickness, cramping and astringent headaches.[123]

Transportation

Some other suicide method is to lie downwards, or throw oneself, in the path of a fast-moving vehicle, either on the road or onto railway tracks. Sometimes a automobile may be driven onto the railway tracks.[124] Nonfatal attempts may upshot in profound injuries, such as multiple bone fractures, amputations, concussion and astringent mental and concrete handicapping.[125]

Route

Some people use intentional car crashes as a suicide method. This especially applies to unmarried-occupant, single-vehicle wrecks,[126] although some suicidal people cause head-on collisions with heavier vehicles.[127] In i report, using a car crash as a suicide method was four times more than likely to kill other people than the average suicide method.[128] Fifty-fifty single-vehicle collisions may harm other road users; for example, a driver who brakes abruptly or swerves to avoid a suicidal person may collide with something else on the route, resulting in damage to the driver or others. Both the targeted commuter and bystanders may be traumatized past the feel, even if anybody survives.

The real per centum of suicides amidst motor vehicle fatalities is non reliably known and probable varies by the ease of accessing a car and the ease of accessing other methods. One review article suggested that more than 2% of crashes upshot from suicidal intent.[129] A study in Switzerland indicated that i% of deaths by suicide involved a motor vehicle collision.[128] A big-scale community survey in Australia among suicidal people indicated that about 20% of men and ten% of women planning a suicide had considered an intentional vehicle wreck, and that a small number had previously attempted a motor vehicle standoff.[130]

Track

On railway tracks above ground, somebody may simply lie downwards or stand on the tracks, equally the speed of an approaching railroad train prevents its like shooting fish in a barrel stopping. This blazon of suicide may cause trauma for the railroad train commuter.[104]

Jumping in forepart of an oncoming subway railroad train has a 59% death rate, lower than the ninety% death rate for rail-related suicides.[ citation needed ] This is most likely because trains traveling on open tracks travel relatively quickly, whereas trains arriving at a subway station are decelerating to stop and board passengers.

Data gathered to 2014 showed that there were three,000 suicides and 800 trespass-related injuries on the European railways each year.[104] In the netherlands, as many as 10% of all suicides are rail-related.[131] In Belgium where rail service is oftentimes interrupted due to a loftier level of suicide past rail, families are expected to cover the substantial cost of track network standstill.[132]

A large number of suicides in Japan every year involve the railway system. Suicide by train is seen as a social problem, especially in the larger cities such as Tokyo or Nagoya, considering information technology disrupts railroad train schedules, damages equipment, harms the drivers,[104] and, if one occurs during the morning blitz-hr, causes numerous commuters to arrive late for work. Suicide by train persists despite a common policy among life insurance companies to deny payment to the beneficiary in the event of suicide by train (payment is usually fabricated in the effect of most other forms of suicide). Suicides involving the loftier-speed bullet-train, or Shinkansen are extremely rare, as the tracks are commonly inaccessible to the public (i.e. elevated and/or protected past tall fences with spinous wire) and legislation mandates additional fines confronting the family unit and next-of-kin of the person who died past suicide.[133] Equally in Kingdom of belgium, family members of the person who died by suicide may be expected to cover the cost of rail disruption, which can exist significantly extensive. It has been argued this prevents possible suicide, as the person who is considering suicide would want to spare the family not only the trauma of a lost family member simply too being sued in court.[134]

The U.Due south. Federal Railroad Administration reports that there are 300 to 500 suicides by train each year.[135] The agency as well reported that those suicides on railway rights-of-ways were by people who tended to alive about railroad tracks, were less probable to have access to firearms, and were significantly compromised by both severe mental disorder and substance abuse.[136]

Reduction

A sign at a railroad crossing in the Netherlands promoting a suicide crisis line (113)

Railway-related suicides are rarely impulsive, and this view has led to research on behaviour analysis using CCTV at known hotspots.[137] Some behaviour patterns are implicated such as station-hopping, platform switching, continuing away from others, letting a number of trains go by, and standing close to where trains enter. Surveillance cameras are viewable by railway staff.[137] Media reporting has been linked to increased rails suicide attempts.[137]

Public access to rail tracks may be restricted by the erection of fences. Fencing on both sides of the rails lines are carried out. Other preventive measures are landscaping to create tree and bush hedging every bit a natural fencing, and the installation of prohibitive signage. Fencing and landscaping have shown pregnant reductions in suicide attempts, and signage a lesser reduction. Sometimes vegetation along the tracks can obscure the view of the train driver and the removal of this is also advocated.[104]

The installation of platform screen doors in many stations and countries has significantly decreased the numbers of suicides, notably in Hong Kong. In Japan the utilize of calming blue lights on station platforms is estimated to have resulted in an 84 per cent reduction in suicide attempts.[104]

On the London Underground the presence of a platform drainage pit has been shown to halve the number of deaths from suicide attempts.[104]

Air

At that place have been suicide attacks by shipping, including Japanese Kamikaze attacks in the Second World War, and the terrorist initiated September 11 attacks in 2001.

Toward the end of the 20th century, one or 2 pilots in the US died by suicide by aircraft each twelvemonth.[138] The pilot was ordinarily flying alone at the time, and was using booze or drugs most half the fourth dimension.[138] [139] In the rare case of a pilot engaging in murder–suicide, the number of innocent people is sometimes very high. On 24 March 2015, a Germanwings co-pilot deliberately crashed Germanwings Flight 9525 into the French Alps to impale himself, killing 150 people with him.[140] [141] Suicide past pilot has also been proposed as a potential cause for the disappearance and following devastation of Malaysian Airlines Flight 370 in 2014,[142] with supporting evidence beingness found in a flight simulator application used by the flying'due south pilot.[143]

Affliction

In that location accept been documented cases of gay men deliberately trying to contract a illness such as HIV/AIDS equally a means of suicide.[144] [145] [146]

Electrocution

Suicide past electrocution involves using a lethal electric stupor, and is a rarely used method.[147] This causes arrhythmias of the heart, meaning that the eye does non contract in synchrony betwixt the dissimilar chambers, essentially causing elimination of blood flow. Furthermore, depending on the current, burns may besides occur. In his opinion outlawing the electrical chair as a method of execution, Justice William One thousand. Connolly of the Nebraska Supreme Court stated that "electrocution inflicts intense pain and agonizing suffering", adding that it is "unnecessarily fell in its purposeless infliction of concrete violence and mutilation of the prisoner's body."[148] Contact with 20 mA of electric current can result in death.[149]

Fire

Cocky-immolation is suicide usually by fire. This method of suicide is rare due to its existence long and painful. If the attempt is intervened, severe burns and scar tissue volition prevail with subsequent emotional touch on. It has been used as a protest tactic, by Thích Quảng Đức in 1963 to protest the South Vietnam's anti-Buddhist policies; by Malachi Ritscher in 2006 to protestation the Us' interest in the Iraq War; by Mohamed Bouazizi in 2011 in Tunisia which gave rise to the Tunisian Revolution;[150] and historically as a ritual known as sati where a Hindu widow would immolate herself in her hubby'due south funeral pyre.[151]

Animal attacks

Some people have chosen to indirectly bring nearly their death past suicide past being attacked past predatory animals. Multiple people have intentionally been killed and eaten by crocodiles.[152] [153]

Several creatures, such as spiders, snakes, and scorpions, produce venom that can impale a person. Although it is uncommon, there have been several cases of suicide or attempted suicide by cobra seize with teeth.[154] [155] While Cleopatra's crusade of death is oftentimes contested, information technology is widely believed that she had an asp bite her when she heard of Marc Antony'south death.[156]

Volcano jumping

Jumping into a volcanic crater is a rare method of suicide. Mount Mihara in Nihon briefly became a notorious suicide site during the Great Depression following media reports of a suicide there. Copycat suicides in the ensuing years prompted the erection of a protective argue surrounding the crater.[157] [158] [159]

Skydiving

There take been several documented cases of suicide by skydiving, by deliberately failing to open a parachute, or removing it during freefall.[160] [161]

Hypothermia

Hypothermia is a rare method of suicide. As of 2015, in that location take been only 9 cases in the scientific literature.[162]

Indirect

Indirect suicide is the act of setting out on an obviously fatal grade without directly carrying out the act upon oneself. Indirect suicide is differentiated from legally defined suicide by the fact that the player does not pull the figurative (or literal) trigger. Examples of indirect suicide include a soldier enlisting in the army with the intention and expectation of beingness killed in combat, or provoking an armed law enforcement officeholder into using lethal force against them. The latter is generally chosen "suicide past cop".

Evidence exists for suicide past capital crime in colonial Australia. Convicts seeking to escape their brutal treatment would murder another private. This was felt necessary due to a religious taboo against direct suicide. A person completing suicide was believed to be destined for hell, whereas a person committing murder could be absolved of their sins before execution. In its nigh farthermost form, groups of prisoners on the extremely roughshod penal colony of Norfolk Island would form suicide lotteries. Prisoners would depict straws with one prisoner murdering another. The remaining participants would witness the crime, and would be sent away to Sydney, every bit majuscule trials could not be held on Norfolk Isle, thus earning a break from the Isle. There is dubiousness as to the extent of suicide lotteries. While surviving contemporary accounts claim that the practice was common, such claims are probably exaggerated.[163]

Rituals

Ritual suicide is performed in a prescribed manner, unremarkably involving fasting, and often as part of a religious or cultural practise.

Seppuku, also known every bit harakiri, is a historical Japanese ritual suicide method involving inflicting a severe wound to the abdomen. For example, Yukio Mishima died past seppuku in 1970 after a failed coup d'état intended to restore total power to the Japanese emperor.[164] The ritual was seen in the Japanese civilization of the time as a means of saving confront.

Encounter also

- Advocacy of suicide

- List of suicides from antiquity to the present

- List of suicides in the 21st century

- Sarco device

- Suicide legislation

References

- ^ "Preventing Suicide |Violence Prevention|Injury Center|CDC". www.cdc.gov. 11 September 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Suicide: 1 person dies every 40 seconds". World Wellness Organization. nine September 2019.

- ^ a b "Method Used in Completed Suicide". HKJC Heart for Suicide Research and Prevention, University of Hong Kong. 2006. Archived from the original on 10 September 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Conner, Andrew; Azrael, Deborah; Miller, Matthew (3 Dec 2019). "Suicide Case-Fatality Rates in the United states, 2007 to 2014". Register of Internal Medicine. 171 (12): 885–895. doi:10.7326/M19-1324. PMID 31791066. S2CID 208611916.

- ^ a b c d e f Turecki, Gustavo; Brent, David A. (nineteen March 2016). "Suicide and suicidal behaviour". Lancet. 387 (10024): 1227–39. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(xv)00234-2. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC5319859. PMID 26385066.

- ^ a b Yip, Paul S. F.; Caine, Eric; Yousuf, Saman; Chang, Shu-Sen; Wu, Kevin Chien-Chang; Chen, Ying-Yeh (23 June 2012). "Means restriction for suicide prevention". Lancet. 379 (9834): 2393–99. doi:x.1016/S0140-6736(12)60521-2. ISSN 1474-547X. PMC6191653. PMID 22726520.

- ^ "Worrying trends in U.S. suicide rates".

- ^ "Suicide". www.who.int . Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ Santaella-Tenorio, J; Cerdá, M; Villaveces, A; Galea, S (2016). "What Do We Know About the Clan Between Firearm Legislation and Firearm-Related Injuries?". Epidemiologic Reviews. 38 (one): 140–57. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxv012. PMC6283012. PMID 26905895.

- ^ a b Berk, Michele (12 March 2019). Bear witness-Based Treatment Approaches for Suicidal Adolescents: Translating Scientific discipline Into Exercise. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 309. ISBN978-1-61537-163-1.

- ^ a b "WHO | First WHO report on suicide prevention calls for coordinated activeness to reduce suicides worldwide". WHO. Archived from the original on eighteen October 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ "Campaign materials – handouts". world wide web.who.int. Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ Carmichael, Victoria; Whitley, Rob (9 May 2019). "Media coverage of Robin Williams' suicide in the United States: A contributor to contamination?". PLOS 1. fourteen (5): e0216543. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1416543C. doi:x.1371/journal.pone.0216543. PMC6508639. PMID 31071144.

- ^ "Reporting on Suicide: Recommendations for the Media". American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Archived from the original on 31 October 2004. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k 50 Wasserman, Danuta (xiv January 2016). Suicide: An unnecessary death. Oxford Academy Press. pp. 359–361. ISBN978-0-19-102683-6.

- ^ Solomon, Andrew (ix June 2018). "Anthony Bourdain, Kate Spade, and the Preventable Tragedies of Suicide". New Yorker . Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "Online Media". Reporting on Suicide. Archived from the original on x Jan 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ Yip, PS; Caine, E; Yousuf, S; Chang, SS; Wu, KC; Chen, YY (23 June 2012). "Means restriction for suicide prevention". Lancet. 379 (9834): 2393–nine. doi:x.1016/S0140-6736(12)60521-2. PMC6191653. PMID 22726520.

- ^ a b Pierpoint, Lauren A; Tung, Gregory J; Brooks-Russell, Ashley; Brandspigel, Sara; Betz, Marian; Runyan, Carol Due west (September 2019). "Gun retailers as storage partners for suicide prevention: what barriers need to be overcome?". Injury Prevention. 25 (Suppl i): i5–i8. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042700. ISSN 1353-8047. PMC6081260. PMID 29436398.

- ^ a b c Rabin, Roni Caryn (17 November 2020). "'How Did We Not Know?' Gun Owners Confront a Suicide Epidemic". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ a b "QuickStats: Age-Adapted Suicide Rates for Females and Males, past Method – National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2000 and 2014". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (xix): 503. 2016. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6519a7. PMID 27197046.

- ^ a b "Suicides in the Great britain". www.ons.gov.uk – Office for National Statistics.

- ^ "Nitschke's suicide machine slammed". world wide web.abc.net.au. 17 December 2008.

- ^ Kurzban, Robert (vii February 2011). "Why Can't You lot Agree Your Breath Until You're Dead?". Web . Retrieved 23 Baronial 2013.

- ^ "Deaths Involving the Inadvertent Connexion of Air-line Respirators to Inert Gas Supplies".

- ^ Goldstein Thou (December 2008). "Carbon monoxide poisoning". Journal of Emergency Nursing. 34 (6): 538–42. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2007.xi.014. PMID 19022078.

- ^ Howard Yard, Hall K, Jeffrey D et al., "Suicide past Asphyxiation due to Helium Inhalation, Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2010; accessed 12 May 2014

- ^ Park, Subin; Ahn, Myung Hee; Lee, Ahrong; Hong, Jin Pyo (4 June 2014). "Associations between changes in the pattern of suicide methods and rates in Korea, the U.s.a., and Finland". International Periodical of Mental Health Systems. 8: 22. doi:10.1186/1752-4458-viii-22. ISSN 1752-4458. PMC4062645. PMID 24949083.

- ^ Ronald W. Maris; Alan Fifty. Berman; Morton M. Silverman; Bruce Michael Bongar (2000). Comprehensive Textbook of Suicidology. Guildford Printing. p. 96. ISBN978-one-57230-541-0.

- ^ a b c Lee, Sing; et al. (2003), "Suicide every bit Resistance in Chinese Society", Chinese Guild: Change, Disharmonize and Resistance, Abingdon: Routledge, p. 297, ISBN9780415301701 .

- ^ Lee, Jonathan H.10.; et al. (2011), Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife, ABC-CLIO, p. eleven, ISBN9780313350672 .

- ^ Lee, Evelyn (1997), Working with Asian Americans: A Guide for Clinicians, Guilford Press, p. 59, ISBN9781572305700 .

- ^ Bourne, P Grand (Baronial 1973). "Suicide amongst Chinese in San Francisco". American Journal of Public Health. 63 (viii): 744–50. doi:x.2105/AJPH.63.8.744. PMC1775294. PMID 4719540.

- ^ "Poisoning methods". Ctrl-c.liu.se. Retrieved fifteen January 2012.

- ^ Ministry of Terror – The Jonestown Cult Massacre, Elissayelle Haney, Infoplease, 2006.

- ^ a b "Share of suicide deaths from pesticide poisoning". Our Earth in Information . Retrieved four March 2020.

- ^ Bertolote, J. M.; Fleischmann, A.; Eddleston, K.; Gunnell, D. (September 2006). "Deaths from pesticide poisoning: a global response". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 189 (3): 201–03. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020834. PMC2493385. PMID 16946353.

- ^ "Underlying Crusade of Death, 1999–2018 Asking". wonder.cdc.gov . Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ Griffiths, Daniel (4 June 2007). "Rural Red china's suicide trouble". BBC News . Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- ^ a b Kim, Jinyong; Shin, Sang Do; Jeong, Seungmin; Suh, Gil Joon; Kwak, Young Ho (2 November 2017). "Event of prohibiting the use of Paraquat on pesticide-associated mortality". BMC Public Health. 17 (i): 858. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4832-4. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC5667494. PMID 29096617.

- ^ Hvistendahl, M. (2013). "In Rural Asia, Locking Upward Poisons to Prevent Suicides". Scientific discipline. 341 (6147): 738–39. Bibcode:2013Sci...341..738H. doi:x.1126/science.341.6147.738. PMID 23950528.

- ^ "Suicides in England and Wales – Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk.

- ^ Brock, Anita; Sini Dominy; Clare Griffiths (vi November 2003). "Trends in suicide by method in England and Wales, 1979 to 2001". Health Statistics Quarterly. 20: 7–18. ISSN 1465-1645. Retrieved 25 June 2007.

- ^ a b Chiew, AL; Gluud, C; Brok, J; Buckley, NA (23 February 2018). "Interventions for paracetamol (acetaminophen) overdose". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (2): CD003328. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003328.pub3. PMC6491303. PMID 29473717.

- ^ Aminoshariae, A; Khan, A (May 2015). "Acetaminophen: old drug, new issues". Periodical of Endodontics. 41 (5): 588–93. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2015.01.024. PMID 25732401.

- ^ Philip Nitschke. The Peaceful Pill Handbook. Exit International U.s., 2007. ISBN 0-9788788-2-5, p. 33

- ^ Guide to a Humane Self-Chosen Expiry past Dr. Pieter Admiraal et al. WOZZ Foundation www.wozz.nl, Delft, The netherlands. ISBN 90-78581-01-8.

- ^ Docker, C (2013). V Terminal Acts – The Get out Path. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 368. ISBN978-1482594096.

- ^ Hay, Phillipa J; Denson, Linley A; van Hoof, Miranda; Blumenfeld, Natalia (Baronial 2002). "The neuropsychiatry of carbon monoxide poisoning in attempted suicide". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 53 (2): 699–708. doi:ten.1016/S0022-3999(02)00424-5. PMID 12169344.

- ^ Nitschke, Philip (2007). The peaceful pill handbook (New rev. international ed.). Waterford, MI: Go out International United states. ISBN978-0978878825.

- ^ Vossberg B, Skolnick J (1999). "The role of catalytic converters in auto carbon monoxide poisoning: a case report". Chest. 115 (2): 580–81. doi:x.1378/chest.115.2.580. PMID 10027464. S2CID 34394596.

- ^ a b "Taking the easy manner out?". South Cathay Morning Postal service. 9 Jan 2005. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Howe, A. (2003). "Media influence on suicide". BMJ. 326 (7387): 498. doi:ten.1136/bmj.326.7387.498. PMC1125377. PMID 12609951.

- ^ "Japanese girl commits suicide with detergent". Archived from the original on 29 April 2008.

- ^ "Mr. A. Braxton Hicks held an inquiry at Battersea". Times [London, England]. 25 September 1894. p. 10.

- ^ "Suicides By Poison". The British Medical Journal. one (1693): 1238. 1893. JSTOR 20224772.

- ^ Lester, D. (March 1990). "Changes in the methods used for suicide in xvi countries from 1960 to 1980". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 81 (iii): 260–61. doi:ten.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb06492.x. PMID 2343750. S2CID 28751662.

- ^ Grinshteyn, Erin; Hemenway, David (March 2016). "Violent Decease Rates: The US Compared with Other High-income OECD Countries, 2010". The American Journal of Medicine. 129 (3): 266–73. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.025. PMID 26551975.

- ^ "Suicide rate by firearm". Our World in Data . Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ "NIMH » Suicide". www.nimh.nih.gov . Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ "A review of suicide statistics in Australia". Authorities of Australia.

- ^ McIntosh, JL; Drapeau, CW (28 November 2012). "U.S.A. Suicide: 2010 Official Final Information" (PDF). suicidology.org. American Clan of Suicidology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 25 Feb 2014.

- ^ Backous, Douglas (v August 1993). "Temporal Bone Gunshot Wounds: Evaluation and Direction". Baylor College of Medicine. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008.

- ^ Mann, JJ; Michel, CA (1 Oct 2016). "Prevention of Firearm Suicide in the Usa: What Works and What Is Possible". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 173 (ten): 969–79. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16010069. PMID 27444796.

- ^ Reisch, Thomas (2013). "Change in Suicide Rates in Switzerland Before and After Firearm Brake Resulting From the 2003 "Army XXI" Reform". American Journal of Psychiatry. 170 (9): 977–984. doi:ten.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12091256. PMID 23897090.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Janet (2012). "Gun utopias? Firearm access and ownership in Israel and Switzerland". Periodical of Public Health Policy. 33 (one): 46–58. doi:10.1057/jphp.2011.56. PMC3267868. PMID 22089893.

- ^ Anestis, Michael D.; Khazem, Lauren R.; Police force, Keyne C.; Houtsma, Claire; LeTard, Rachel; Moberg, Fallon; Martin, Rachel (Oct 2015). "The Clan Between State Laws Regulating Handgun Ownership and Statewide Suicide Rates". American Journal of Public Wellness. 105 (10): 2059–67. doi:ten.2105/AJPH.2014.302465. PMC4566551. PMID 25880944.

- ^ Conner, Kenneth R; Zhong, Yueying (November 2003). "State firearm laws and rates of suicide in men and women". American Periodical of Preventive Medicine. 25 (4): 320–24. doi:ten.1016/S0749-3797(03)00212-5. PMID 14580634.

- ^ Westefeld, John South.; Gann, Lianne C.; Lustgarten, Samuel D.; Yeates, Kevin J. (2016). "Relationships betwixt firearm availability and suicide: The part of psychology". Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 47 (4): 271–77. doi:10.1037/pro0000089.

- ^ Anglemyer, Andrew; Horvath, Tara; Rutherford, George (21 January 2014). "The Accessibility of Firearms and Risk for Suicide and Homicide Victimization Amid Household Members". Register of Internal Medicine. 160 (2): 101–x. doi:x.7326/M13-1301. PMID 24592495. S2CID 4509567.

- ^ Miller, M.; Swanson, Due south. A.; Azrael, D. (13 January 2016). "Are We Missing Something Pertinent? A Bias Assay of Unmeasured Confounding in the Firearm-Suicide Literature". Epidemiologic Reviews. 38 (1): 62–9. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxv011. PMID 26769723.

- ^ Lewiecki, E. Michael; Miller, Sara A. (January 2013). "Suicide, Guns, and Public Policy". American Journal of Public Health. 103 (ane): 27–31. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300964. PMC3518361. PMID 23153127.

- ^ "Guns and suicide: A fatal link". Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. 15 May 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Studdert, David Yard.; Zhang, Yifan; Swanson, Sonja A.; Prince, Lea; Rodden, Jonathan A.; Holsinger, Erin; Spittal, Matthew; Wintemute, Garen; Miller, Matthew (2020). "Handgun Ownership and Suicide in California". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (23): 2220–29. doi:x.1056/NEJMsa1916744. PMID 32492303.

- ^ Committee on Law and Justice (2004). "Executive Summary". Firearms and Violence: A Critical Review. National University of Science. doi:10.17226/10881. ISBN978-0-309-09124-4.

- ^ Kellermann, A.L.; Rivara, F.P.; Somes, G.; Francisco, Jerry; et al. (1992). "Suicide in the habitation in relation to gun buying". New England Journal of Medicine. 327 (7): 467–72. doi:10.1056/NEJM199208133270705. PMID 1308093. S2CID 35031090.

- ^ a b Miller, Matthew; Hemenway, David (2001). Firearm Prevalence and the Risk of Suicide: A Review. Harvard Health Policy Review. p. 2.

I study institute a statistically significant relationship between estimated gun ownership levels and suicide rate across 14 developed nations (eastward.m. where survey data on gun ownership levels were bachelor), merely the association lost its statistical significance when boosted countries were included.

- ^ Birckmayer, Johanna; Hemenway, David (September 2001). "Suicide and Firearm Prevalence: Are Youth Disproportionately Affected?". Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 31 (3): 303–10. doi:10.1521/suli.31.iii.303.24243. PMID 11577914.

- ^ Miller, Matthew; Hemenway, David (March 1999). "The relationship between firearms and suicide". Aggression and Violent Behavior. 4 (1): 59–75. doi:10.1016/S1359-1789(97)00057-eight.

- ^ Brent, D. A.; Bridge, J. (1 May 2003). "Firearms Availability and Suicide: Bear witness, Interventions, and Time to come Directions". American Behavioral Scientist. 46 (9): 1192–1210. doi:10.1177/0002764202250662. S2CID 72451364.

- ^ Briggs, Justin Thomas; Tabarrok, Alexander (March 2014). "Firearms and suicides in The states states". International Review of Law and Economics. 37: 180–88. CiteSeerX10.1.1.453.3579. doi:x.1016/j.irle.2013.10.004.

- ^ a b Miller, Matthew; Warren, Molly; Hemenway, David; Azrael, Deborah (April 2015). "Firearms and suicide in U.s.a. cities". Injury Prevention. 21 (e1): e116–e119. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2013-040969. PMID 24302479. S2CID 3275417.

- ^ Miller, Thou.; Barber, C.; White, R. A.; Azrael, D. (23 August 2013). "Firearms and Suicide in the United States: Is Adventure Independent of Underlying Suicidal Beliefs?". American Journal of Epidemiology. 178 (half dozen): 946–55. doi:10.1093/aje/kwt197. PMID 23975641.

- ^ Miller, K (one June 2006). "The association between changes in household firearm ownership and rates of suicide in the U.s., 1981–2002". Injury Prevention. 12 (3): 178–82. doi:x.1136/ip.2005.010850. PMC2563517. PMID 16751449.

- ^ Miller, Matthew; Lippmann, Steven J.; Azrael, Deborah; Hemenway, David (April 2007). "Household Firearm Buying and Rates of Suicide Beyond the l United States". The Periodical of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 62 (iv): 1029–35. doi:10.1097/01.ta.0000198214.24056.twoscore. PMID 17426563.

- ^ Anestis, MD; Houtsma, C (thirteen March 2017). "The Association Between Gun Ownership and Statewide Overall Suicide Rates". Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 48 (ii): 204–17. doi:ten.1111/sltb.12346. PMID 28294383. S2CID 4756779.

- ^ Stroebe, Wolfgang (November 2013). "Firearm possession and violent death: A critical review". Aggression and Violent Behavior. eighteen (half-dozen): 709–21. doi:x.1016/j.avb.2013.07.025. hdl:10419/214553.

- ^ Siegel, Michael; Rothman, Emily F. (July 2016). "Firearm Ownership and Suicide Rates Among The states Men and Women, 1981–2013". American Journal of Public Health. 106 (7): 1316–22. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303182. PMC4984734. PMID 27196643.

- ^ Cook, Philip J.; Ludwig, Jens (2000). "Chapter 2". Gun Violence: The Real Costs . Oxford Academy Press. ISBN978-0-nineteen-513793-4.

- ^ Ikeda, Robin Yard.; Gorwitz, Rachel; James, Stephen P.; Powell, Kenneth E.; Mercy, James A. (1997). Fatal Firearm Injuries in the United states of america, 1962–1994: Violence Surveillance Summary Series, No. 3. National Centre for Injury and Prevention Command.

- ^ Anglemyer, A; Horvath, T; Rutherford, G (21 January 2014). "The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-assay". Annals of Internal Medicine. 160 (2): 101–10. doi:10.7326/M13-1301. PMID 24592495. S2CID 4509567.

- ^ Chapman, S; Alpers, P; Agho, K; Jones, Thou (one December 2006). "Australia'south 1996 gun law reforms: faster falls in firearm deaths, firearm suicides, and a decade without mass shootings". Injury Prevention. 12 (6): 365–372. doi:x.1136/ip.2006.013714. PMC2704353. PMID 17170183.

- ^ Caron, Jean (Oct 2004). "Gun Control and Suicide: Possible Touch on of Canadian Legislation to Ensure Safe Storage of Firearms". Archives of Suicide Research. 8 (4): 361–74. doi:ten.1080/13811110490476752. PMID 16081402. S2CID 35131214.

- ^ Caron, Jean; Julien, Marie; Huang, Jean Hua (April 2008). "Changes in Suicide Methods in Quebec between 1987 and 2000: The Possible Bear on of Bill C-17 Requiring Safe Storage of Firearms". Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 38 (two): 195–208. doi:ten.1521/suli.2008.38.2.195. PMID 18444777.

- ^ Cheung, AH; Dewa, CS (2005). "Current trends in youth suicide and firearms regulations". Canadian Journal of Public Health. 96 (2): 131–35. doi:ten.1007/BF03403676. PMC6975744. PMID 15850034.

- ^ Beautrais, A. Fifty.; Fergusson, D. K.; Horwood, L. J. (26 June 2016). "Firearms Legislation and Reductions in Firearm-Related Suicide Deaths in New Zealand". Australian & New Zealand Periodical of Psychiatry. 40 (3): 253–59. doi:10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01782.x. PMID 16476153. S2CID 208623661.

- ^ Beautrais, Annette Fifty.; Joyce, Peter R.; Mulder, Roger T. (26 June 2016). "Access to Firearms and the Risk of Suicide: A Example Control Study". Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 30 (6): 741–748. doi:10.3109/00048679609065040. PMID 9034462. S2CID 9805679.

- ^ "Firearms, Accidental Deaths, Suicides and Trigger-happy Crime: An Updated Review of the Literature with Special Reference to the Canadian Situation". x March 1999.

- ^ Langmann, C. (2020). "Effect of firearms legislation on suicide and homicide in Canada from 1981 to 2016". PLOS I. xv (six): e0234457. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1534457L. doi:10.1371/periodical.pone.0234457. PMC7302582. PMID 32555647.

- ^ "BBC Inside Out - Suicide spot". www.bbc.co.u.k. . Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ ""Jumping" and Suicide Prevention". Heart for Suicide Prevention.

- ^ Koopman, John (2 Nov 2005). "LETHAL BEAUTY / No easy death: Suicide by span is gruesome, and expiry is almost certain. The fourth in a 7-office series on the Gold Gate Bridge barrier debate". San Francisco Chronicle . Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- ^ a b "WISQARS Leading Causes of Expiry Reports". Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f yard Havârneanu, GM; Burkhardt, JM; Paran, F (August 2015). "A systematic review of the literature on safety measures to preclude railway suicides and trespassing accidents". Blow Analysis and Prevention. 81: xxx–fifty. doi:x.1016/j.aap.2015.04.012. PMID 25939134.

- ^ "遭家人責罵:掛住上網媾女唔讀書 成績跌出三甲 中四生跳樓亡". Apple tree Daily. 9 Baronial 2009. Retrieved x September 2009.

- ^ Pounder, Derrick. "Lecture Notes in Forensic Medicine" (PDF). p. vi. Archived from the original (PDF) on xiv June 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ^ a b c Kisch, T; Matzkeit, Northward; Waldmann (May 2019). "The Reason Matters: Deep Wrist Injury Patterns Differ with Intentionality (Accident versus Suicide Endeavor)". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Global Open. 7 (five): e2139. doi:ten.1097/GOX.0000000000002139. PMC6571333. PMID 31333923.

- ^ Baker, Susan P.; O'Neill, Brian; Ginsburg, Marvin J.; Li, Guohua (1991). The Injury Fact Book. Oxford University Press. p. 65. ISBN978-0-19-974870-9.

- ^ Bukhari, AJ; Saleem, Grand; Bhutta, AR; Khan, AZ; Abid, KJ (Oct 2004). "Spaghetti wrist: management and outcome". Journal of the Higher of Physicians and Surgeons Islamic republic of pakistan. 14 (10): 608–11. doi:10.2004/JCPSP.608611 (inactive 28 February 2022). PMID 15456551.

{{cite periodical}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of February 2022 (link) - ^ Gruenewald, DA (September 2018). "Voluntarily Stopping Eating and Drinking: A Practical Approach for Long-Term Intendance Facilities". Journal of Palliative Medicine. 21 (ix): 1214–20. doi:10.1089/jpm.2018.0100. PMID 29870302. S2CID 46943176.

- ^ a b Pope, Thaddeus Mason; Anderson, Lindsey E. (7 October 2010), Voluntarily Stopping Eating and Drinking: A Legal Treatment Option at the End of Life, SSRN 1689049

- ^ Sheldon, T (21 June 2008). "Dutch doctors publish guide to "careful suicide"". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 336 (7658): 1394–95. doi:x.1136/bmj.a362. PMC2432148. PMID 18566058.

- ^ Docker C, The Fine art and Science of Fasting in: Smith C, Docker C, Hofsess J, Dunn B, Beyond Terminal Exit 1995

- ^ Sundara, A. "Nishidhi Stones and the ritual of Sallekhana" (PDF). International Schoolhouse for Jain Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ "Hinduism – Euthanasia and Suicide". BBC. 25 Baronial 2009.

- ^ Greer, John Michael (2003). The New Encyclopedia of the Occult. ISBN978-1567183368 . Retrieved 4 Feb 2014 – via Google Books.

- ^ Radford, Tim (19 April 2002). "Thor Heyerdahl dies at 87". The Guardian. London. Retrieved half dozen July 2009.

- ^ Baumrucker, Steven (five September 2016). "Scientific discipline, hospice, and terminal dehydration". American Periodical of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. sixteen (3): 502–03. doi:10.1177/104990919901600302. PMID 10661057. S2CID 44883936.

- ^ Bernat, James L. (27 December 1993). "Patient Refusal of Hydration and Diet". Archives of Internal Medicine. 153 (24): 2723–28. doi:ten.1001/archinte.1993.00410240021003. PMID 8257247. S2CID 36848946.

- ^ Miller, Franklin G.; Meier, Diane Eastward. (2004). "Voluntary Decease: A Comparison of Terminal Dehydration and Doctor-Assisted Suicide". Register of Internal Medicine. 128 (7): 559–62. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-128-seven-199804010-00007. PMID 9518401. S2CID 34734585.

- ^ Jacobs, Sandra (24 July 2003). "Decease by Voluntary Aridity – What the Caregivers Say". New England Periodical of Medicine. 349 (4): 325–26. doi:ten.1056/NEJMp038115. PMID 12878738.

- ^ Arehart-Treichel, Joan (xvi Jan 2004). "Terminally Ill Choose Fasting Over Grand.D.-Assisted Suicide". Psychiatric News. 39 (two): fifteen–51. doi:10.1176/pn.39.two.0015.

- ^ Smith, Wesley J. (12 November 2003). "A 'Painless' Death?". The Weekly Standard.

- ^ Hilkevitch, Jon (iv July 2004). "When expiry rides the rails". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 20 December 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2009.

- ^ Ricardo Alonso-Zaldivar (26 January 2005). "Suicide past Train Is a Growing Business organization". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Selzer, Thou. L.; Payne, C. E. (1992). "Motorcar accidents, suicide, and unconscious motivation". American Journal of Psychiatry. 119 (3): 237–forty [239]. doi:x.1176/ajp.119.three.237. PMID 13910542. S2CID 46631419.

- ^ Evans, Leonard. "Commuter beliefs". Science Serving Social club. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ a b Gauthier, Saskia; Reisch, Thomas; Ajdacic-Gross, Vladeta; Bartsch, Christine (2015). "Route Traffic Suicide in Switzerland". Traffic Injury Prevention. 16 (8): 768–772. doi:10.1080/15389588.2015.1021419. ISSN 1538-957X. PMID 25793638. S2CID 205884989.

- ^ Pompili, K; Serafini, G; Innamorati, K; et al. (xxx November 2012). "Car accidents as a method of suicide: a comprehensive overview". Forensic Science International. 223 (1–3): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.04.012. PMID 22576104.

- ^ Murray, D.; de Leo, D. (September 2007). "Suicidal behavior by motor vehicle collision". Traffic Inj Prev. eight (3): 244–47. doi:10.1080/15389580701329351. PMID 17710713. S2CID 30149719.

- ^ Netherlands, Statistics. "Suicide death rate upwards to i,647". www.cbs.nl.

- ^ "Les suicides coûtent 2 millions à la SNCB qui tente de se faire rembourser auprès des familles". sudinfo.exist.

- ^ French, Howard W. (six June 2000). "Kunitachi City Journal; Japanese Trains Try to Shed a Gruesome Appeal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 27 June 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ New, Ultra Super. "Claret on the tracks: Who pays for deadly railway accidents? | Yen for Living".

- ^ Noah Bierman (9 February 2010). "Striving to prevent suicide by train". Boston.com. Boston Earth.

- ^ Martino, Michael et al. (2013). Defining Characteristics of Intentional Fatalities on Railway Rights-of-Way in the U.s., 2007–2010. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Railroad Administration.

- ^ a b c Mishara, BL; Bardon, C (15 March 2016). "Systematic review of research on railway and urban transit system suicides". Journal of Melancholia Disorders. 193: 215–26. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.042. PMID 26773913.

- ^ a b Bills, Corey B.; Grabowski, Jurek George; Li, Guohua (2005). "Suicide by Aircraft: A Comparative Analysis". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 76 (8): 715–xix. PMID 16110685.

- ^ Kenedi, Christopher; Friedman, Susan Hatters; Watson, Dougal; Preitner, Claude (one Apr 2016). "Suicide and Murder-Suicide Involving Aircraft". Aerospace Medicine and Human Performance. 87 (4): 388–396. doi:10.3357/AMHP.4474.2016. ISSN 2375-6314. PMID 27026123.

- ^ Clark, Nicola; Bilefsky, Dan (26 March 2015). "Germanwings Co-Airplane pilot Deliberately Crashed Airbus Jet, French Prosecutor Says". The New York Times . Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ "Germanwings Flight 4U9525: Co-pilot put plane into descent, prosecutor says". CBC News. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ Wescott, Richard (16 April 2015). "Flying MH370: Could information technology take been suicide?". BBC News. BBC News. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ Pells, Rachael (23 July 2016). "MH370 pilot flew 'suicide road' on a simulator 'closely matching' his final flight". The Independent. The Independent. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ Frances, Richard J.; Wikstrom, Thomas; Alcena, Valiere (1985). "Contracting AIDS as a means of committing suicide". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 142 (5): 656. doi:10.1176/ajp.142.v.656b. PMID 3985206.

- ^ Flavin, Daniel Yard.; Franklin, John E.; Frances, Richard J. (1986). "The acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and suicidal beliefs in alcohol-dependent homosexual men". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 143 (11): 1440–42. doi:10.1176/ajp.143.11.1440. PMID 3777237. S2CID 21218263.

- ^ Ronald Due west. Maris; Alan L. Berman; Morton M. Silverman; Bruce M. Bongar (2000). Comprehensive textbook of suicidology. Guilford Printing. p. 161. ISBN978-1-57230-541-0.

- ^ Marc, B; Baudry, F; Douceron, H; Ghaith, A; Wepierre, JL; Garnier, K (Jan 2000). "Suicide by electrocution with depression-voltage current". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 45 (1): 216–22. doi:10.1520/JFS14665J. PMID 10641944.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (9 February 2008). "Electrocution Is Banned in Last State to Rely on Information technology". The New York Times. Archived from the original on eleven Feb 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ Fish, RM; Geddes, LA (12 October 2009). "Conduction of electrical current to and through the human trunk: a review". ePlasty. ix: e44. PMC2763825. PMID 19907637.

- ^ Fahim, Kareem (21 Jan 2011). "Slap to a Homo'southward Pride Prepare Off Tumult in Tunisia". The New York Times. p. 2. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ Sophie Gilmartin (1997), The Sati, the Bride, and the Widow: Sacrificial Woman in the Nineteenth Century, Victorian Literature and Culture, Cambridge Academy Press, Vol. 25, No. 1, p. 141, Quote: "Suttee, or sati, is the obsolete Hindu practice in which a widow burns herself upon her husband's funeral pyre..."

- ^ "Thai adult female eaten by crocodiles". news.bbc.co.uk. 11 August 2002.

- ^ "Thai adult female in crocodile pit suicide". BBC News. 16 September 2014.

- ^ "Texas man committed suicide using venomous snake, government say". Reuters. xiii Nov 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ Mallik, Subhendu; Singh, Sudipta Ranjan; Mohanty, Manoj Kumar; Padhy, Niranjan (October 2016). "Attempted suicide by snake seize with teeth: A instance study". Medicine, Science, and the Law. 56 (4): 264–266. doi:ten.1177/0025802416659160. ISSN 2042-1818. PMID 27417152. S2CID 45316626.

- ^ Come across:

- Strabo, Geographica, Book 17, Chapter ane, paragraph 10: Octavian "forced Antony to put himself to expiry and Cleopatra to come up into his power live; only a little later she too put herself to death secretly, while in prison, by the seize with teeth of an asp or (for two accounts are given) by applying a poisonous ointment" …

- Sextus Propertius, Elegies, Book 3, number xi: … "I saw your [Cleopatra's] arms bitten past the sacred asps, and your limbs draw sleep in by a hugger-mugger path." … Available on-line at: Poetry in Translation

- Horace, Odes, Volume i, Ode 37: … "And she [Cleopatra] dared to gaze at her fallen kingdom / with a calm face up, and impact the poisonous asps / with courage, and then that she might drink down / their dark venom, to the depths of her heart," … Bachelor on-line at: Poetry in Translation

- Virgil, Aeneid, Volume 8, lines 696–697: … "The queen in the centre signals to her columns with the native sistrum, not even so turning to look at the twin snakes at her back." … Available on-line at: Poetry in Translation

- ^ Cedric A. Mims (1998). When nosotros die. Robinson. p. 40. ISBN978-i-85487-529-7.

- ^ Edward Robb Ellis; George N. Allen (1961). Traitor within: our suicide trouble. Doubleday. p. 98.

- ^ "Jumpers". The New Yorker. 13 October 2003.

- ^ West.M. Eckert; Westward.Due south. Reals (1978). "Air disaster investigation". Legal Medicine Annual: 57–70. PMID 756947.

- ^ David Dolinak; Evan W. Matshes; Emma O. Lew (2005). Forensic pathology: principles and practise. Academic Press. p. 293. ISBN978-0-12-219951-half-dozen.

- ^ Wilcoxon, Rebecca; Jackson, Lorren; Baker, Andrew (i September 2015). "Suicide by Hypothermia: A Written report of 2 Cases and 23-Year Retrospective Review". Academic Forensic Pathology. v (iii): 462–475. doi:10.23907/2015.051. S2CID 79722611. Retrieved 25 Dec 2021.

- ^ Hughes, Robert (1988). The Fatal Shore, The Epic Story of Australia's Founding (beginning ed.). Vintage Books.

- ^ Nathan, John. Mishima: A biography, Little Chocolate-brown and Visitor: Boston/Toronto, 1974.

Further reading

- Humphry, Derek (1997). Final Exit: The Practicalities of Self-Deliverance and Assisted Suicide for the Dying. Dell. p. 240.

- Nitschke, Philip (2007). The Peaceful Pill Handbook. U.s.a.: Exit International. p. 211. ISBN978-0-9788788-2-5.

- Docker, C. (2015). Five Final Acts - The Get out Path. Scotland: Createspace.

- Stone, G. (2001). Suicide and Attempted Suicide: Methods and Consequences. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN978-0-7867-0940-iii.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suicide_methods

0 Response to "what is an easy painless way to commit suicide"

Postar um comentário